PCA

→ Why do it?

After RNAseq, you're left with a lot of genes to look at, and you wish someone would just tell you which are the important ones. PCA is one way of doing that. It's a method in a family known as 'dimensional reduction', where for RNAseq the dimensions are your genes. It can help guide you as to what genes are driving differences between phenotypes, but it can also be an easy method for quality assurance to make sure your samples of the same experimental group are actually grouping together.

→ How does it work?

I'll be honest: I have not wrapped my head around exactly how PCA does what it does - but I can tell you the gist, and we can interpret the results.

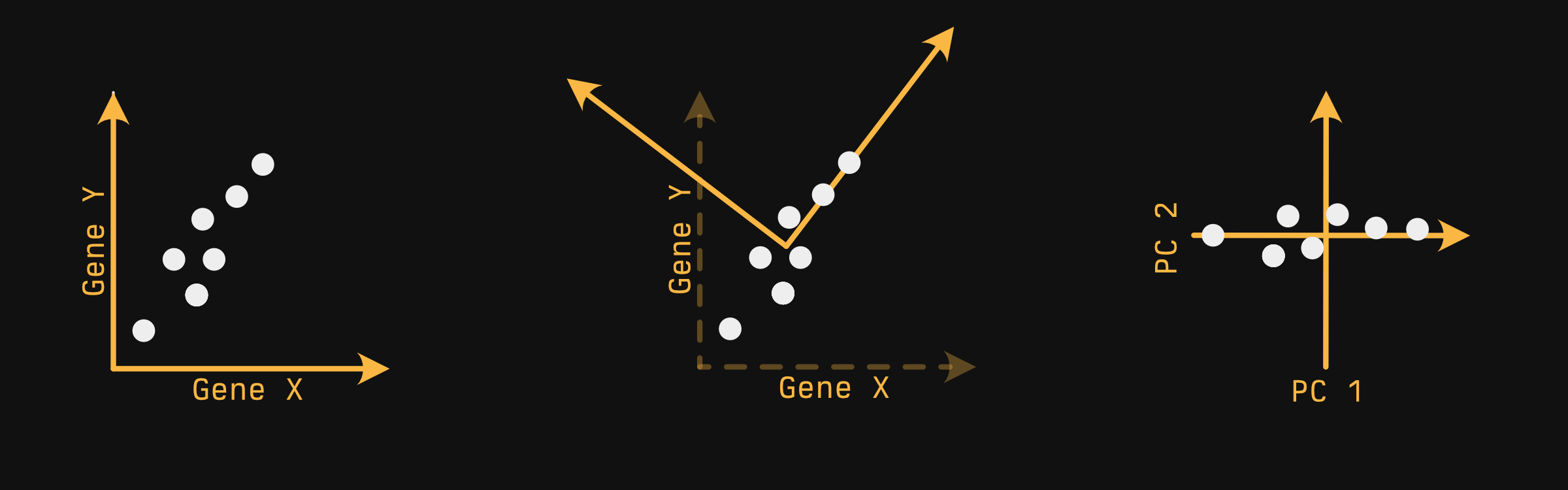

Your data float in N-dimensional space, where N is the number of genes you have expression for. While this number will typically range in the thousands, we can simplify for just a moment down to two genes.

With just two genes, we can represent it via an x-y plane, as shown below (first panel):

Your samples - the white circles - float in a very pedagogically convenient pattern. You can imagine PCA does something like this:

-

Find the axis in which you capture the most variability. Allison Horst described this as 'if you were a whale shark, which way would you rotate your head to get the most krill on a first pass', provided your samples were krill. In a 2-D plane, this looks a lot like fitting a line. This axis is our first principle component.

-

Next, draw a line orthogonal to the first that captures the next most variability. Since we only have two dimensions, we don't have a choice where it goes. If we had a third axis pointing out at us, we'd be able to 'spin' the second axis around the first, out of the screen and into it...but we don't.

-

After this is done for every axis, you generally choose two axes to plot, and this is typically the first and second principal components, since they capture the most variability.

Exactly HOW the PCA algorithm finds these axes is frankly beyond me.

→ Doing it

library(tidyverse)

library(broom)

library(ggsci)

library(ggrepel)

library(cellebrate)

library(DESeq2)

options(crayon.enabled = FALSE) # Keeps formatting pretty for the website.

Another way: tidymodels

You can also perform PCA with tidymodels - it's a bit neater, but woefully more involved if you aren't already familiar with it. If you do any supervised analyses, it may be worth learning the tidymodels ecosystem.→ Penguins

→ Preparing the dataset

Instead of starting with RNAseq data - with its thousands of genes - let's start with something a bit easier and (most importantly) cuter. We're going to use the penguins dataset, which has recently been introduced into base R.

What about `iris`?

If you're familiar with typical R examples, you might be used to seeing the iris dataset - it contains various measurements of flowers of various species, and lets you see how various properties of the flowers can, in combination, be used to classify flower species.

There are a couple reasons for using the penguins dataset instead. First of all, penguins are cute:

Secondly, the dataset does have some ties with eugenics in that although it was not collected by RA Fisher, it was used by him for a paper on linear discriminant analysis, published in the Journal of Eugenics. The dataset is somewhat tainted by association, and since we have another dataset available to us, why not use it?

The penguins data have some missing values, which will cause problems for us later if not removed. complete.cases returns a vector of TRUE and FALSE (that is, a 'logical vector'), TRUE if every value in the row is not NA, FALSE otherwise. We use that to select 'complete' rows.

penguins_no_na <- penguins[complete.cases(penguins), ] |>

as_tibble()

penguins_no_na

# A tibble: 333 × 8

species island bill_len bill_dep flipper_len body_mass sex year

<fct> <fct> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <int> <fct> <int>

1 Adelie Torgersen 39.1 18.7 181 3750 male 2007

2 Adelie Torgersen 39.5 17.4 186 3800 female 2007

3 Adelie Torgersen 40.3 18 195 3250 female 2007

4 Adelie Torgersen 36.7 19.3 193 3450 female 2007

5 Adelie Torgersen 39.3 20.6 190 3650 male 2007

6 Adelie Torgersen 38.9 17.8 181 3625 female 2007

7 Adelie Torgersen 39.2 19.6 195 4675 male 2007

8 Adelie Torgersen 41.1 17.6 182 3200 female 2007

9 Adelie Torgersen 38.6 21.2 191 3800 male 2007

10 Adelie Torgersen 34.6 21.1 198 4400 male 2007

# ℹ 323 more rows

# ℹ Use `print(n = ...)` to see more rows

PCA is generally only done on continuous numeric variables, so let's select those:

penguins_minimal <- penguins_no_na |>

select(bill_len, bill_dep, flipper_len, body_mass)

penguins_minimal

# A tibble: 333 × 4

bill_len bill_dep flipper_len body_mass

<dbl> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 39.1 18.7 181 3750

2 39.5 17.4 186 3800

3 40.3 18 195 3250

4 36.7 19.3 193 3450

5 39.3 20.6 190 3650

6 38.9 17.8 181 3625

7 39.2 19.6 195 4675

8 41.1 17.6 182 3200

9 38.6 21.2 191 3800

10 34.6 21.1 198 4400

# ℹ 323 more rows

# ℹ Use `print(n = ...)` to see more rows

→ Doing PCA

There are actually two PCA functions built in to R: prcomp and princomp. You should use prcomp. They're both essentially the same, but prcomp is slightly more numerically accurate. This generally won't matter for your purposes, but there's really no reason not to use it.

In general, you should scale (standardize, 'z-scorify') your data, but it's off by default (for compatibility with S, the language which R is derived/modeled after). For the same reasons as with hierarchical clustering, it probably makes sense to scale your log'd expression data, too.

Actually doing PCA is R is stupid easy:

pca <- prcomp(penguins_minimal, scale. = TRUE)

pca

Standard deviations (1, .., p=4):

[1] 1.6569115 0.8821095 0.6071594 0.3284579

Rotation (n x k) = (4 x 4):

PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4

bill_len 0.4537532 -0.60019490 -0.6424951 0.1451695

bill_dep -0.3990472 -0.79616951 0.4258004 -0.1599044

flipper_len 0.5768250 -0.00578817 0.2360952 -0.7819837

body_mass 0.5496747 -0.07646366 0.5917374 0.5846861

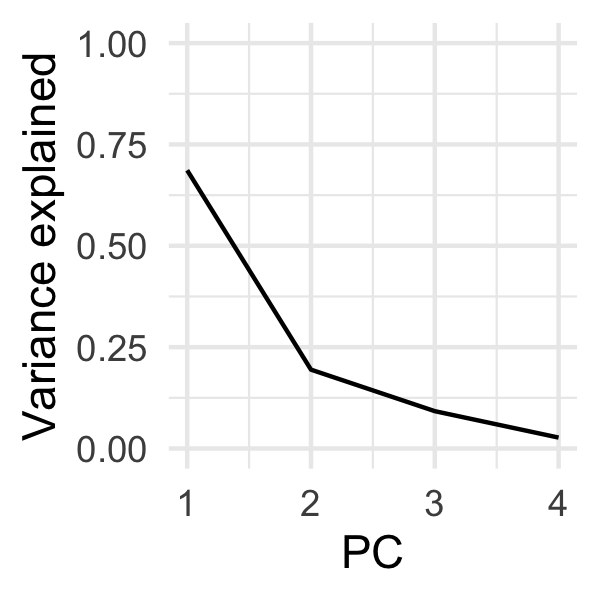

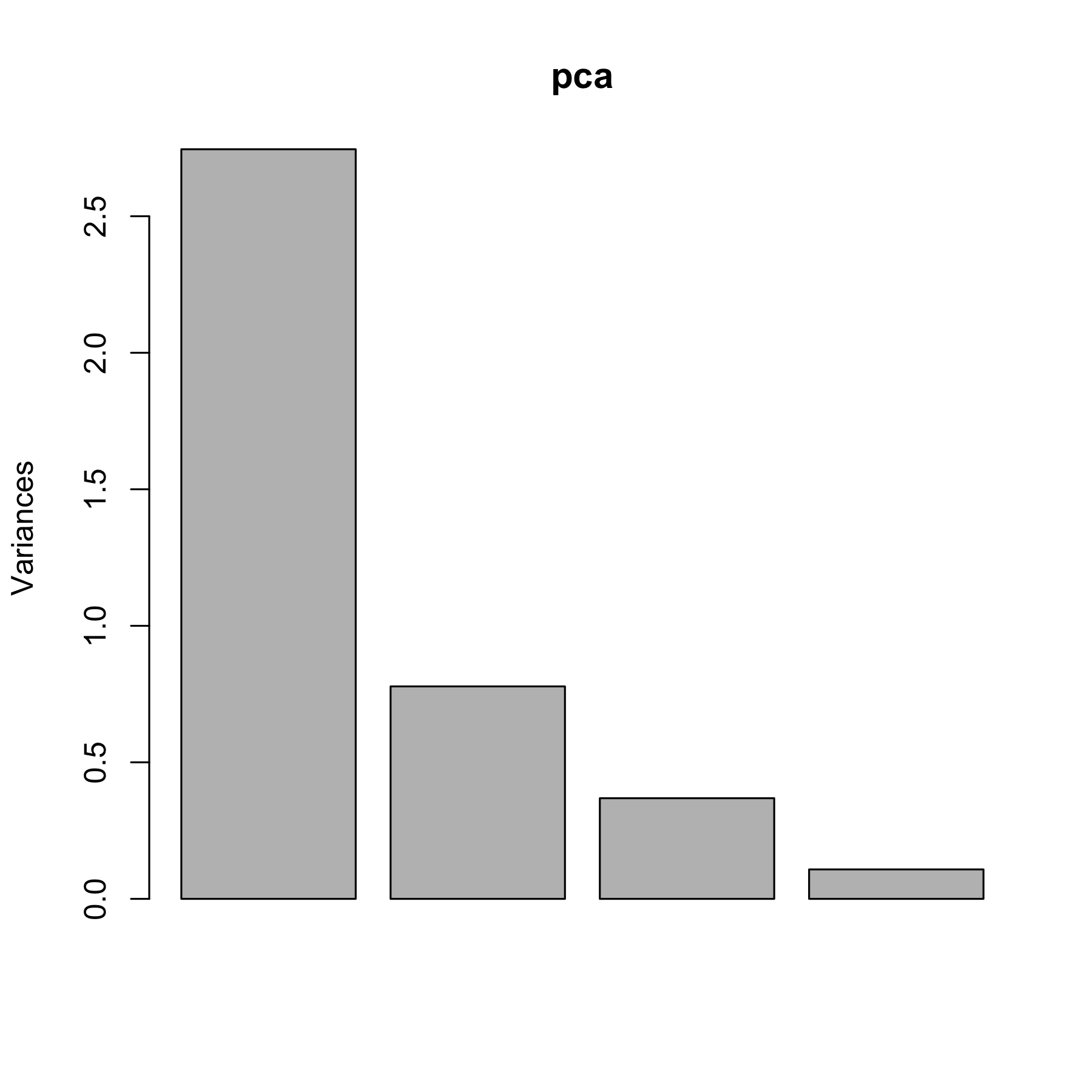

→ Scree plot

You'll notice we have 4 principal components (PC1-4). This is because we had 4 input variables: bill_len, bill_dep, flipper_len, and body_mass. The order of the components is important - the first captures the most variability, the second the second most, and so on. We can observe this more directly with a 'scree plot'.

The venerable broom package will allow us to get at these data painlessly with the tidy function:

var_explained <- tidy(pca, "pcs")

var_explained

# A tibble: 4 × 4

PC std.dev percent cumulative

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 1 1.66 0.686 0.686

2 2 0.882 0.195 0.881

3 3 0.607 0.0922 0.973

4 4 0.328 0.0270 1

Which we can easily plot:

ggplot(var_explained, aes(PC, percent)) +

geom_line() +

theme_minimal() +

coord_cartesian(ylim = c(0, 1)) +

labs(y = "Variance explained")

Scree plots are typically used for determining how many components you would need to capture the brunt of the variability before you start getting diminishing returns. This is typically denoted by a qualitative 'crook' or a 'knee' in the plot. We can kind of see one at PC2, but as we'll see later, PC3 is actually quite valuable for discriminating penguin species.

→ PCA plot

If we want to plot our penguins in principal component space, we need to extract a different slot from our PCA object.

penguin_coords <- pca |>

tidy("samples")

penguin_coords

# A tibble: 1,332 × 3

row PC value

<int> <dbl> <dbl>

1 1 1 -1.85

2 1 2 -0.0320

3 1 3 0.235

4 1 4 0.528

5 2 1 -1.31

6 2 2 0.443

7 2 3 0.0274

8 2 4 0.401

9 3 1 -1.37

10 3 2 0.161

# ℹ 1,322 more rows

# ℹ Use `print(n = ...)` to see more rows

Since I want to plot different PCs on different axes, and since ggplot2 generally expects different axes to be different columns, I'm going to make this dataset 'wider':

penguin_coords <- pivot_wider(

penguin_coords,

names_from = PC,

names_prefix = "PC",

values_from = value

)

penguin_coords

# A tibble: 333 × 5

row PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4

<int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 1 -1.85 -0.0320 0.235 0.528

2 2 -1.31 0.443 0.0274 0.401

3 3 -1.37 0.161 -0.189 -0.528

4 4 -1.88 0.0123 0.628 -0.472

5 5 -1.92 -0.816 0.700 -0.196

6 6 -1.77 0.366 -0.0284 0.505

7 7 -0.817 -0.500 1.33 0.348

8 8 -1.80 0.245 -0.626 0.215

9 9 -1.95 -0.997 1.04 -0.210

10 10 -1.57 -0.577 2.05 -0.263

# ℹ 323 more rows

# ℹ Use `print(n = ...)` to see more rows

I included the names_prefix parameter because otherwise the columns would be numbers. This is technically workable when you use a tibble, but confusing: when plotting with ggplot, I would need to remember to do ggplot(data, aes(`1`, `2`)) instead of ggplot(data, aes(1, 2)), which would not work. I already burned myself once doing this just writing this chapter, so to save you the pain, I'm showing you how to sidestep it.

You'll notice our data doesn't have any information on the penguins - what species they are, for instance. For that, we have to join them back to our original data. The safest way to do this is to 'join' our data, rather than just blindly abutting our data next to one another. This protects against the case in which rows are missing or moved.

The row column of our penguin_coords includes the rownames of our input data. To easily join these data together, we can convert our rownames of our original data into a column, then join based on that column:

penguins_with_rownames <- penguins_no_na |>

rownames_to_column("row") |>

mutate(row = as.numeric(row)) # To make same type as penguin_coords$row

penguins_with_pca_coords <- left_join(

penguins_with_rownames,

penguin_coords,

by = "row"

)

glimpse(penguins_with_pca_coords)

Rows: 333

Columns: 13

$ row <dbl> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17,…

$ species <fct> Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Adelie, Ad…

$ island <fct> Torgersen, Torgersen, Torgersen, Torgersen, Torgersen, Tor…

$ bill_len <dbl> 39.1, 39.5, 40.3, 36.7, 39.3, 38.9, 39.2, 41.1, 38.6, 34.6…

$ bill_dep <dbl> 18.7, 17.4, 18.0, 19.3, 20.6, 17.8, 19.6, 17.6, 21.2, 21.1…

$ flipper_len <int> 181, 186, 195, 193, 190, 181, 195, 182, 191, 198, 185, 195…

$ body_mass <int> 3750, 3800, 3250, 3450, 3650, 3625, 4675, 3200, 3800, 4400…

$ sex <fct> male, female, female, female, male, female, male, female, …

$ year <int> 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007, 2007…

$ PC1 <dbl> -1.8508078, -1.3142762, -1.3745366, -1.8824555, -1.9170957…

$ PC2 <dbl> -0.03202119, 0.44286031, 0.16098821, 0.01233268, -0.816369…

$ PC3 <dbl> 0.23454869, 0.02742880, -0.18940423, 0.62792772, 0.6999979…

$ PC4 <dbl> 0.527602641, 0.401122984, -0.527867518, -0.472182619, -0.1…

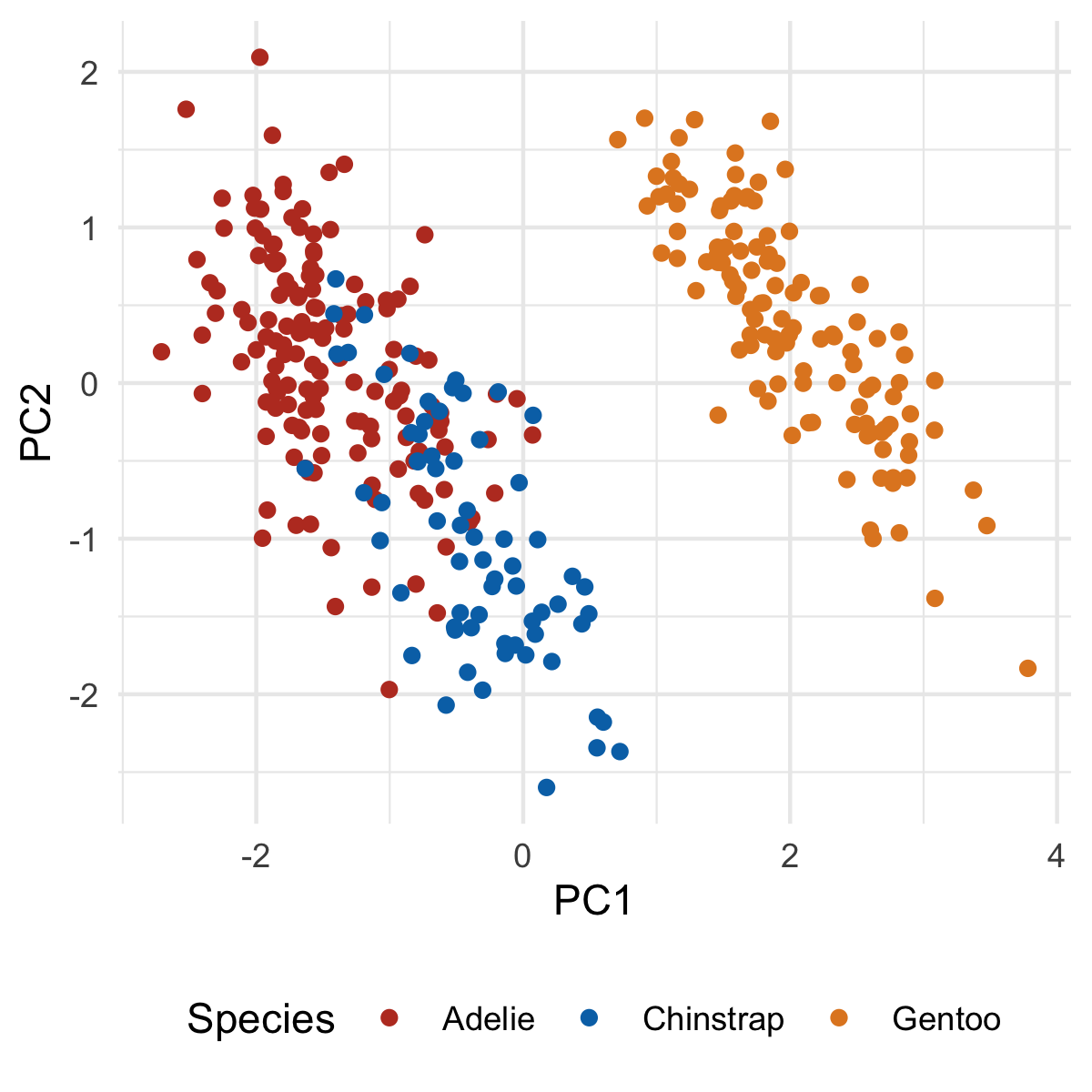

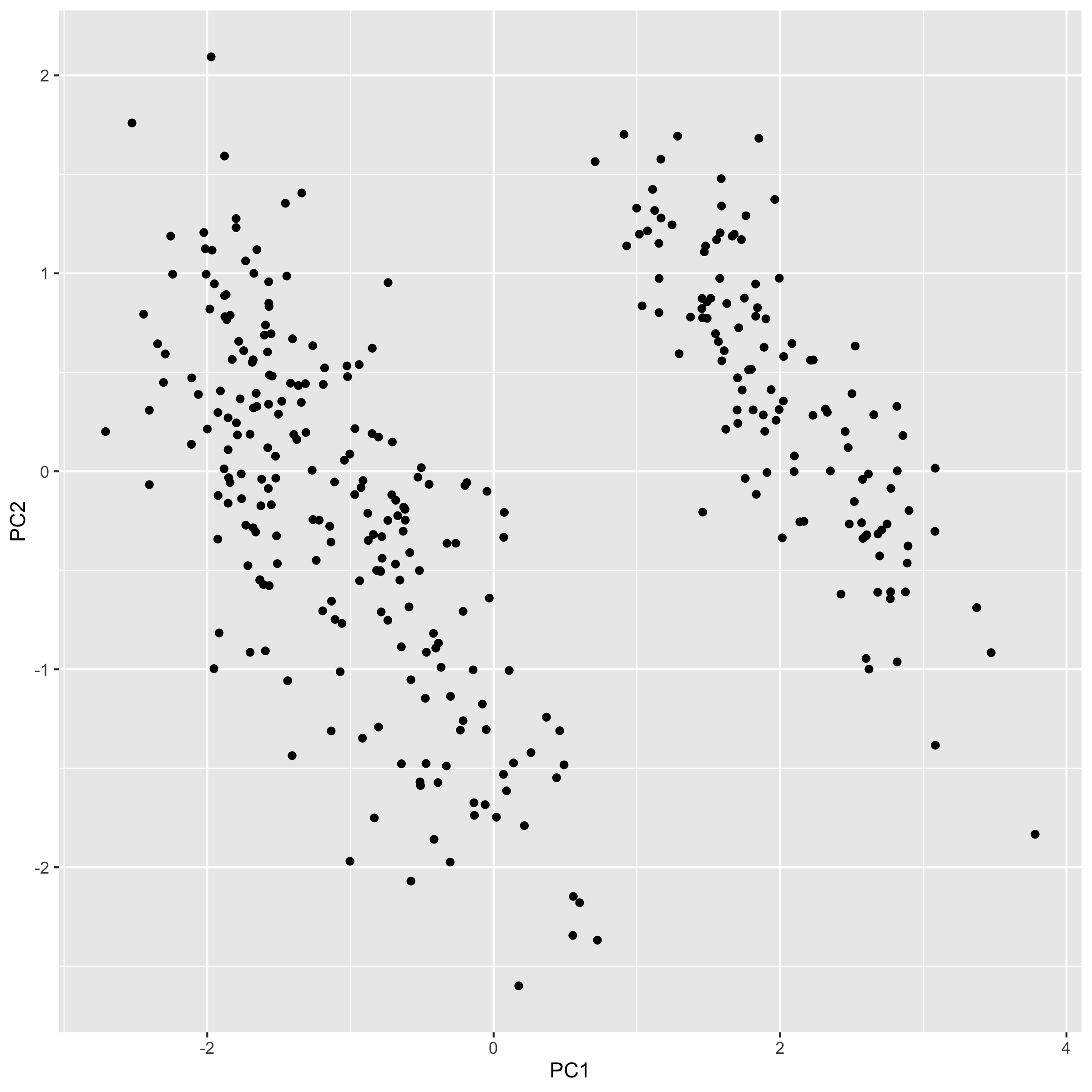

We have enough for a basic plot - let's do so:

ggplot(penguins_with_pca_coords, aes(PC1, PC2)) +

geom_point(aes(color = species)) +

theme_minimal() +

scale_color_nejm() +

labs(color = "Species") +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

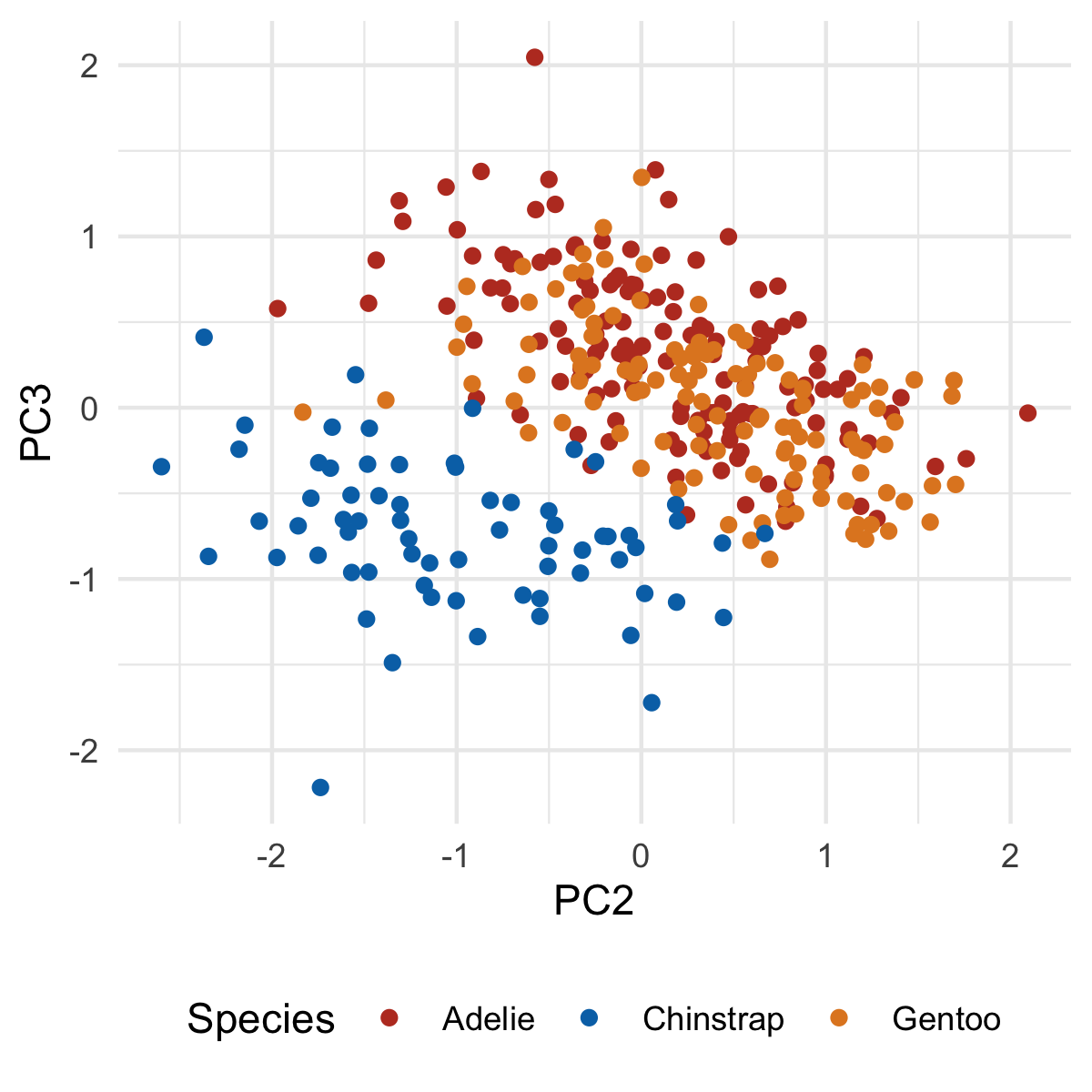

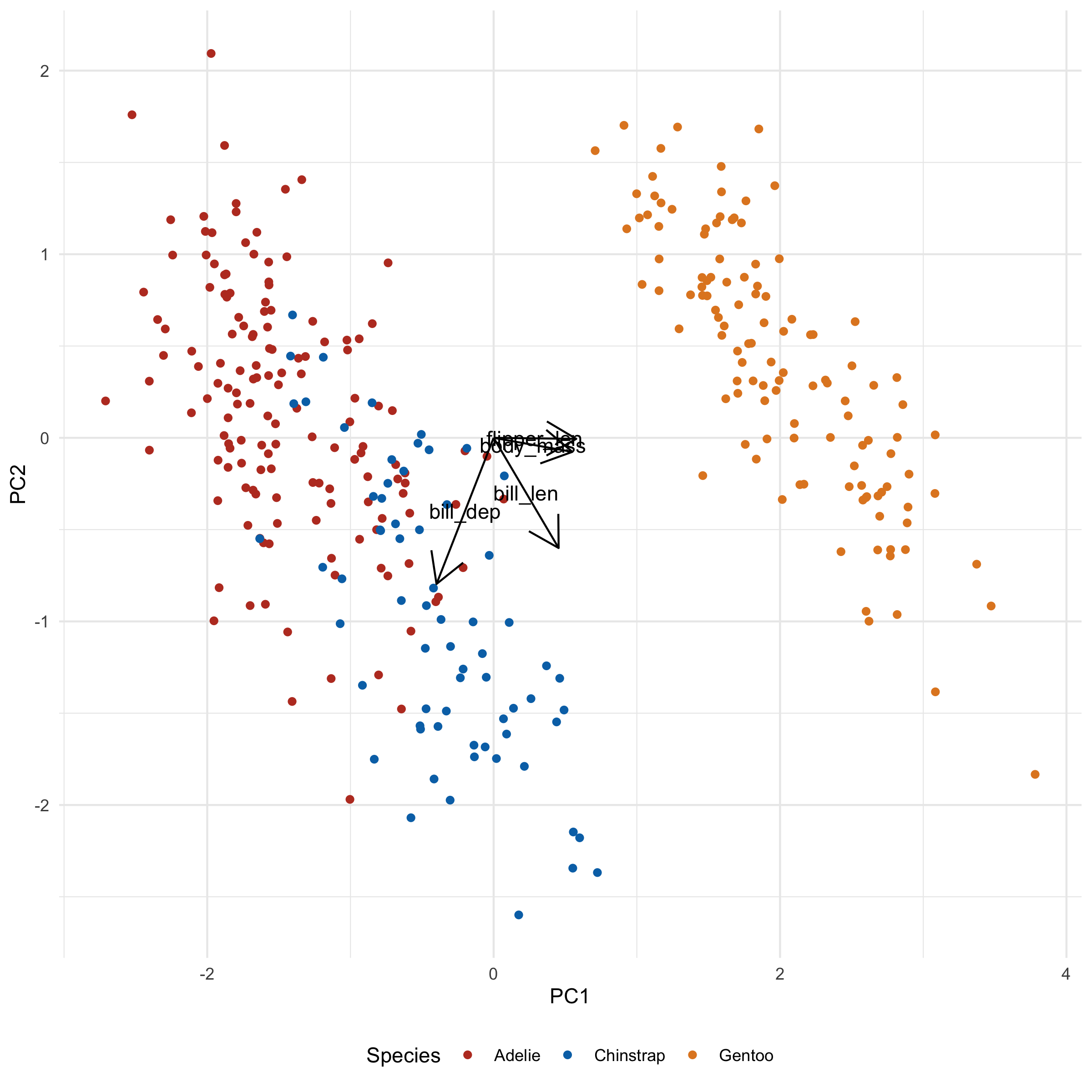

Our first principle component clearly separates Gento from Adelie and Chinstrap. You might be able to surmise what variables are causing this based on the original PCA output, but we'll make this crystal clear when we add our loadings. But first, let's plot PC2 and PC3:

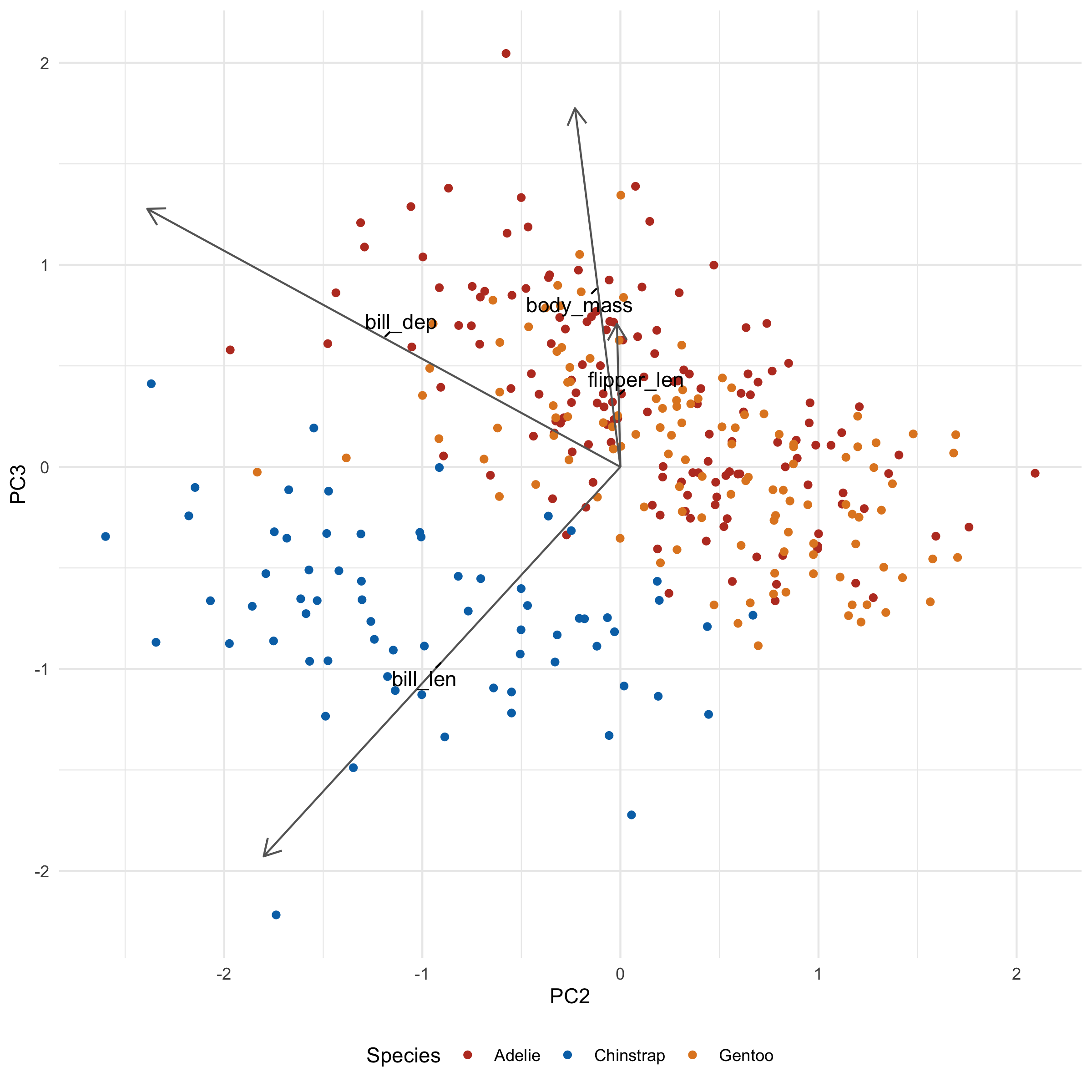

ggplot(penguins_with_pca_coords, aes(PC2, PC3)) +

geom_point(aes(color = species)) +

theme_minimal() +

scale_color_nejm() +

labs(color = "Species") +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

Notice how the third principal component helps separate Chinstrap from everyone else, something that was not seen in the first two principal components.

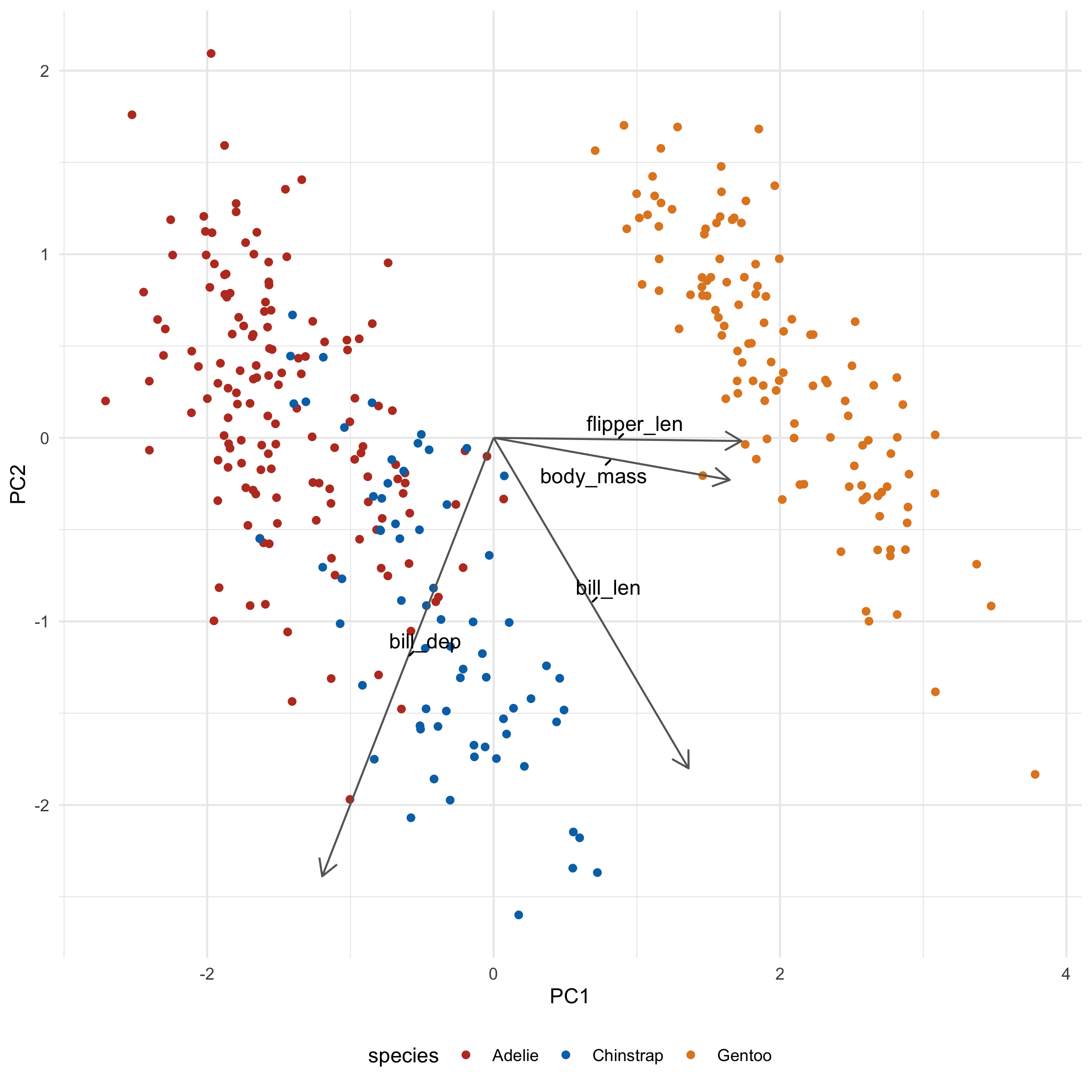

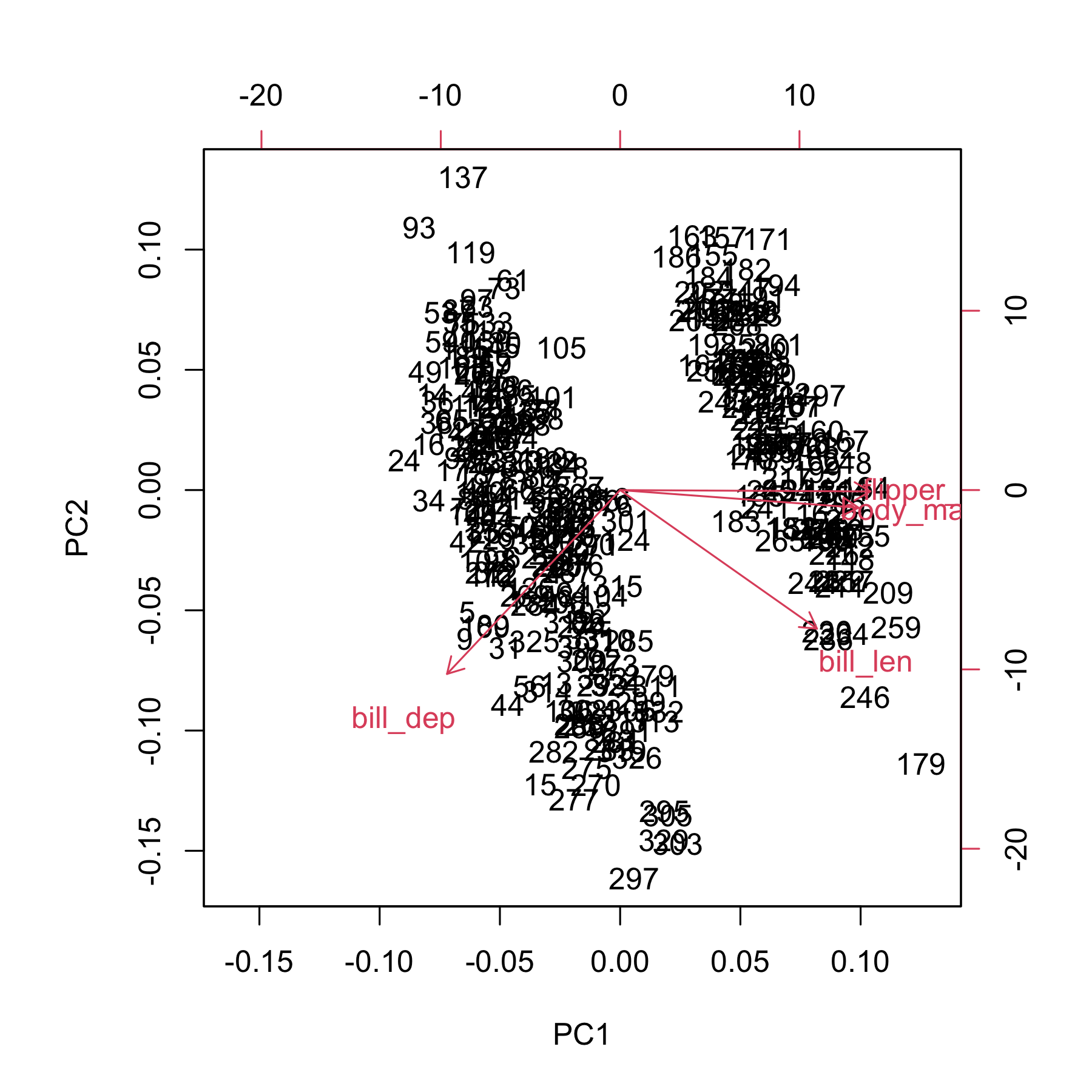

→ Biplot

Sometimes you'll see a PCA plot with arrows overlaid that represent the 'old' axes (that is, the variables within our dataset before PCA). These are useful as they can let you know why a given group separates from one another in terms of the variables you care about, rather than principal components. These plots are called 'biplots'.

→ Doing it badly

To get the directionality of these old axes in the new plane, we need to extract the loadings from our PCA. Again we turn to tidy:

penguin_loadings <- tidy(pca, "loadings")

penguin_loadings

# A tibble: 16 × 3

column PC value

<chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 bill_len 1 0.454

2 bill_len 2 -0.600

3 bill_len 3 -0.642

4 bill_len 4 0.145

5 bill_dep 1 -0.399

6 bill_dep 2 -0.796

7 bill_dep 3 0.426

8 bill_dep 4 -0.160

9 flipper_len 1 0.577

10 flipper_len 2 -0.00579

11 flipper_len 3 0.236

12 flipper_len 4 -0.782

13 body_mass 1 0.550

14 body_mass 2 -0.0765

15 body_mass 3 0.592

16 body_mass 4 0.585

As before, we'll widen our data:

penguin_loadings_wide <- pivot_wider(

penguin_loadings,

names_from = PC,

values_from = value,

names_prefix = "PC"

)

penguin_loadings_wide

# A tibble: 4 × 5

column PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 bill_len 0.454 -0.600 -0.642 0.145

2 bill_dep -0.399 -0.796 0.426 -0.160

3 flipper_len 0.577 -0.00579 0.236 -0.782

4 body_mass 0.550 -0.0765 0.592 0.585

Each row represents the coordinates of an axis in 'PCA space'. Each of these axes is one unit long.

Plotting them isn't hard:

ggplot(penguins_with_pca_coords, aes(PC1, PC2)) +

geom_point(aes(color = species)) +

geom_segment(

data = penguin_loadings_wide,

aes(x = 0, y = 0, xend = PC1, yend = PC2),

arrow = arrow(),

) +

geom_text(

data = penguin_loadings_wide,

aes(x = PC1/2, y= PC2/2, label = column)

) +

theme_minimal() +

scale_color_nejm() +

labs(color = "Species") +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

→ Making it better

This clearly looks bad. Everything we want is there but it's all messed up. However, I wanted to show you the 'bones' of the code before I did anything fancy, so you can associate what code goes with what changes.

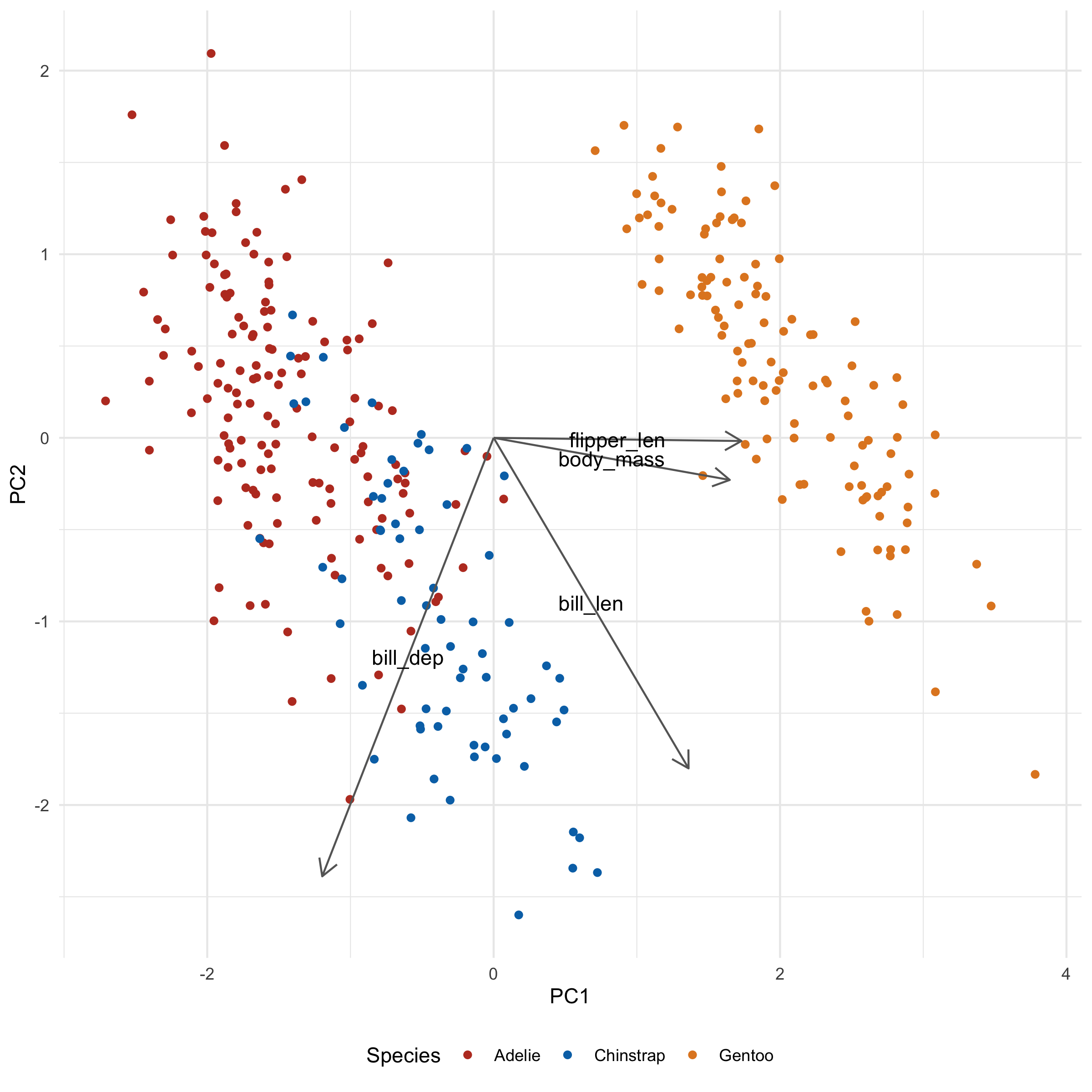

I'm going to make a few changes:

- Shrink the arrowheads

- Make the arrows grayer

- Increase the distance of the arrowheads by scaling the magnitude by a constant

The last step will increase ALL arrows by a factor, so their differences can still be compared. They'll no longer be unit vectors, but I've found that rarely to be useful or important.

ggplot(penguins_with_pca_coords, aes(PC1, PC2)) +

geom_point(aes(color = species)) +

geom_segment(

data = penguin_loadings_wide,

aes(

x = 0, y = 0,

xend = PC1 * 3,

yend = PC2 * 3

),

arrow = arrow(length = unit(0.02, "npc")), # Change 1

color = "gray40" # Change 2

) +

geom_text(

data = penguin_loadings_wide,

aes(

x = PC1 * 3 / 2,

y= PC2 * 3 / 2,

label = column

)

) +

theme_minimal() +

scale_color_nejm() +

labs(color = "Species") +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

There's one additional thing we can do to keep the labels from overlapping, using the ggrepel package. In general, this is as simple as loading the package and converting geom_text to geom_text_repel:

library(ggrepel)

ggplot(penguins_with_pca_coords, aes(PC1, PC2)) +

geom_point(aes(color = species)) +

geom_segment(

data = penguin_loadings_wide,

aes(

x = 0, y = 0,

xend = PC1 * 3,

yend = PC2 * 3

),

arrow = arrow(length = unit(0.02, "npc")), # Change 1

color = "gray40" # Change 2

) +

geom_text_repel(

data = penguin_loadings_wide,

aes(

x = PC1 * 3 / 2,

y= PC2 * 3 / 2,

label = column

),

min.segment.length = 0

) +

theme_minimal() +

scale_color_nejm() +

labs(color = "Species") +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

I also added min.segment.length = 0 so that the labels will always point to where they intended to be. It's a little less tidy looking, but also a little less ambiguous.

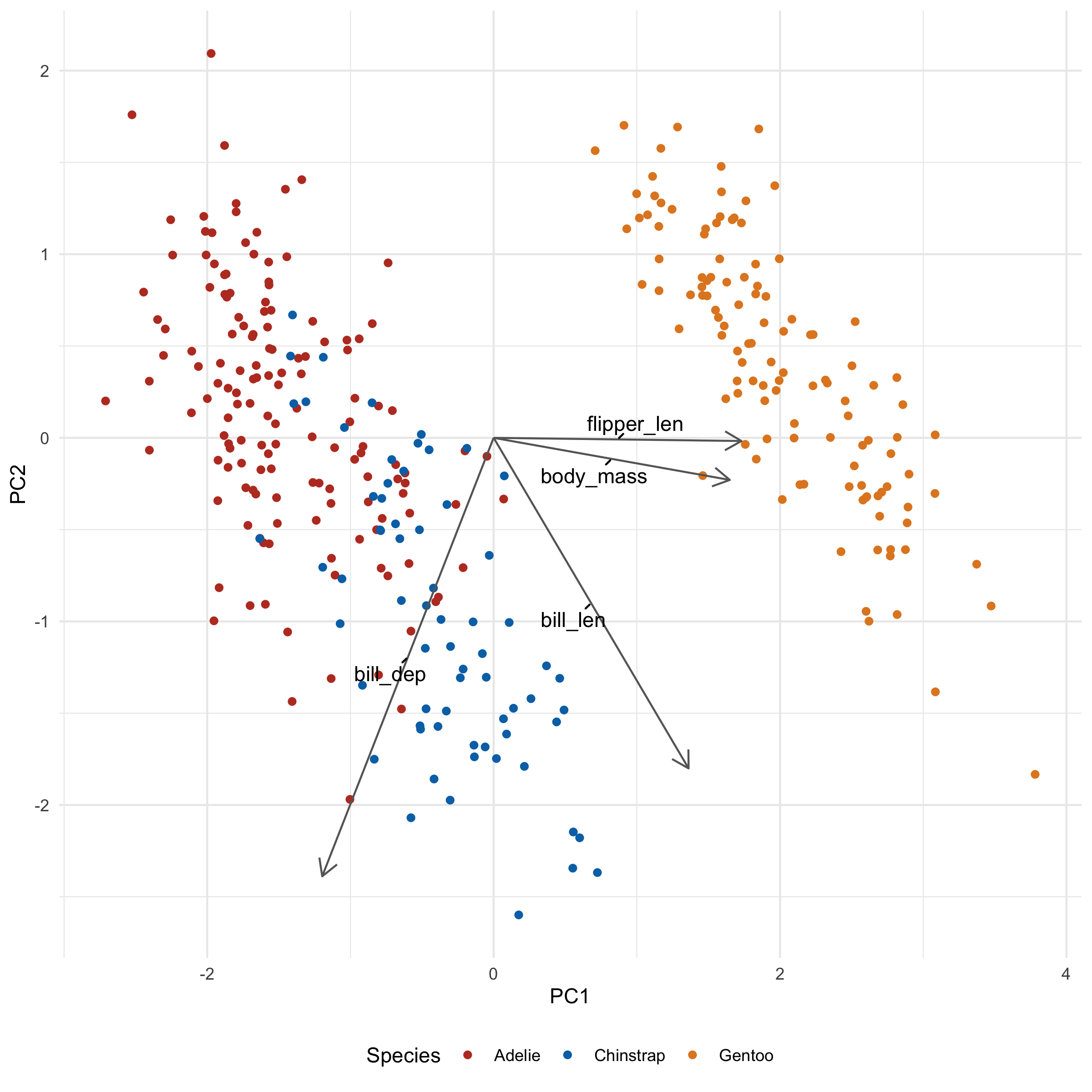

→ What's it all mean?

Let's take a look at what these loadings imply for a second. flipper_len and body_mass is pointing towards Gentoo, and indeed, Gentoo penguins are relatively huge. We also note that bill_len appears to be pointing along the Adelie/Chinstrap gradient, implying that it will be an important determinant for separating the two groups. Indeed, when we plot across PC2 and PC3 we see just that:

library(ggrepel)

ggplot(penguins_with_pca_coords, aes(PC2, PC3)) +

geom_point(aes(color = species)) +

geom_segment(

data = penguin_loadings_wide,

aes(

x = 0, y = 0,

xend = PC2 * 3,

yend = PC3 * 3

),

arrow = arrow(length = unit(0.02, "npc")),

color = "gray40"

) +

geom_text_repel(

data = penguin_loadings_wide,

aes(

x = PC2 * 3 / 2,

y= PC3 * 3 / 2,

label = column

),

min.segment.length = 0

) +

theme_minimal() +

scale_color_nejm() +

labs(color = "Species") +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

→ Make it a function

Before we move on to biological data, let's turn this into a function that we can apply to both our penguins and cell data.

One tricky aspect of making this function is that we want to include which principal component columns we choose to plot as some of our arguments. However, if we did something like this:

my_plot_function <- function(data, x, y) {

ggplot(data, aes(x, y)) +

geom_point()

}

...this would actually fail:

my_plot_function(penguins_with_pca_coords, PC1, PC2)

# Error in `geom_point()`:

# ! Problem while computing aesthetics.

# ℹ Error occurred in the 1st layer.

# Caused by error:

# ! object 'PC1' not found

# Run `rlang::last_trace()` to see where the error occurred.

The reasons for this are complex. For the curious, the answer is explained best here. Essentially, you need to 'smuggle' the arguments in and evaluate them at the right time and place. This is done via 'embracing', using {{. This WILL work:

my_fixed_plot_function <- function(data, x, y) {

ggplot(data, aes({{ x }}, {{ y }})) +

geom_point()

}

my_fixed_plot_function(penguins_with_pca_coords, PC1, PC2)

Applying this to our old plots, we can make a function like this:

plot_pca <- function(data, x, y, color_column, loadings, loadings_scale_factor) {

ggplot(data, aes({{ x }}, {{ y }})) +

geom_point(aes(color = {{ color_column }})) +

geom_segment(

data = loadings,

aes(

x = 0, y = 0,

xend = {{ x }} * loadings_scale_factor,

yend = {{ y }} * loadings_scale_factor

),

arrow = arrow(length = unit(0.02, "npc")),

color = "gray40"

) +

geom_text_repel(

data = loadings,

aes(

x = {{ x }} * loadings_scale_factor / 2,

y = {{ y }} * loadings_scale_factor / 2,

label = column

),

min.segment.length = 0,

max.overlaps = 20

) +

theme_minimal() +

scale_color_nejm() +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

}

plot_pca(penguins_with_pca_coords, PC1, PC2, species, penguin_loadings_wide, 3)

The code inside the body of the function isn't much different from the code we used to make PCA plots previously:

-

I factored out the columns that determine the x and y axes and color (using the embrace (

{{) operator), - I've made the loadings dataset a parameter

-

I added a

loadings_scale_factorparameter. We want to be able to adjust this easily since with different datasets, the amount we need to 'expand' our loadings varies wildly (we'll see this in the next section)

→ Biological Data

With gene expression data you will have as many loading arrows as you have genes. Obviously you can't plot all these - it would be a mess - so we should filter for the loadings that have the largest magnitude in the directions we're interested in.

filter_loadings <- function(loadings, PC_A, PC_B, n) {

# This function keeps the largest n magnitude loadings for both PCs

# It may return < 2*n loadings if both PCs 'pick' the same loading

# This is kind of a clunky bit of code, but I can't think of a better way.

loadings |>

arrange(abs({{ PC_A }})) |>

mutate(keep1 = rep(c(F, T), times = c(nrow(loadings) - n, n))) |>

arrange(abs({{ PC_B }})) |>

mutate(keep2 = rep(c(F, T), times = c(nrow(loadings) - n, n))) |>

filter(keep1 | keep2) |>

select(-keep1, -keep2)

}

filter_loadings(penguin_loadings_wide, PC1, PC2, 1)

# A tibble: 2 × 5

column PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 flipper_len 0.577 -0.00579 0.236 -0.782

2 bill_dep -0.399 -0.796 0.426 -0.160

Instead of adding all our loadings to the plotting function we made, we'll supply this filtered version instead.

Let's crack open our bladder cancer data yet again:

norm_expression_mat <- cell_rna |>

vst() |>

assay()

You'll want to put 'cases' as the rows. For our penguins, each row was a penguin. In its default state, each row for gene expression data is usually a gene not a sample, the unit of information we probably actually want to plot. If you forget this, you will end up with a plot that has thousands of points and you will know exactly what happened.

As such, we need to transpose our data before performing PCA:

expression_t <- t(norm_expression_mat)

cell_pca <- prcomp(expression_t, scale. = TRUE)

cell_pca_coordinates <- tidy(cell_pca) |>

pivot_wider(names_from = PC, values_from = value, names_prefix = "PC")

glimpse(cell_pca_coordinates, width = 80)

Rows: 30

Columns: 31

$ row <chr> "1A6", "253JP", "5637", "BV", "HT1197", "HT1376", "J82", "RT112",…

$ PC1 <dbl> -30.4016292, -58.0065914, -8.1335313, -60.4156153, 12.6108078, 7.…

$ PC2 <dbl> 25.422972, -94.171977, 17.701357, -95.397621, 49.532125, 41.57211…

$ PC3 <dbl> -34.7859242, 11.3884243, 10.8426700, -5.0198760, -12.5433371, -14…

$ PC4 <dbl> 36.4225319, -31.6204152, 17.5611424, -14.0397713, -78.3832224, -5…

$ PC5 <dbl> -19.642001, 44.477496, -3.017162, 42.059930, -40.303520, 28.25040…

$ PC6 <dbl> 8.368505, 49.212232, -17.330220, 27.888599, 4.533926, 1.268254, 1…

$ PC7 <dbl> -17.8911448, -1.8845112, -14.1458187, -0.7710756, 78.3709353, 16.…

$ PC8 <dbl> 27.3671786, -11.4932896, 42.6486138, -22.3213518, -38.4741319, -4…

$ PC9 <dbl> -56.7361483, -28.1344320, -51.7406404, -18.5778316, -48.3198031, …

$ PC10 <dbl> -17.7075529, 3.4238317, -31.8406325, 1.3956879, 3.9090899, -31.66…

$ PC11 <dbl> 9.6226812, 1.6364261, -1.3693397, -5.0885048, 4.3576782, 8.537502…

$ PC12 <dbl> 23.8847443, -7.8611541, 27.8736451, 17.7834193, -8.5471293, 32.20…

$ PC13 <dbl> 27.0640293, 0.2385481, 13.1363628, 5.1689289, 15.4297454, 10.3767…

$ PC14 <dbl> 13.5280527, -1.7371398, 1.8211620, -4.4539946, -36.2292842, 84.05…

$ PC15 <dbl> -27.196216, -11.263094, -20.157926, 5.136542, 16.441383, -9.81334…

$ PC16 <dbl> -14.588707, -7.122114, 13.635063, 15.501592, 15.353886, -6.486275…

$ PC17 <dbl> -12.280303, -13.755056, -3.346803, 3.534963, -16.665870, 23.77536…

$ PC18 <dbl> 0.9971822, -5.5524044, 13.7704522, -10.1022629, -5.4025588, 19.40…

$ PC19 <dbl> 19.2977995, -6.8518302, 3.2161952, 1.2270500, 19.0531323, -19.101…

$ PC20 <dbl> 8.0045187, 6.0505044, 0.5478513, -5.3040131, -12.9695349, 2.32992…

$ PC21 <dbl> -24.47504766, 11.83423626, -13.72046315, -12.52451891, 0.02440866…

$ PC22 <dbl> -13.9249794, 13.8372928, -1.0101539, -11.4612989, -0.5870471, -5.…

$ PC23 <dbl> 10.916880, -11.924624, -3.024771, 14.938580, 2.390969, 3.417330, …

$ PC24 <dbl> 19.8599398, -13.8228683, -23.4916323, 12.3353783, -2.8490657, 0.8…

$ PC25 <dbl> 3.6609106, 46.0697855, 10.6853402, -48.0530521, 1.3379030, 2.8025…

$ PC26 <dbl> 4.39734493, 15.94679083, 1.04179343, -19.41591581, -3.16765954, 2…

$ PC27 <dbl> 1.0991013, -15.1101868, 2.2419781, 18.6521758, 2.3587801, 1.41629…

$ PC28 <dbl> -9.52773211, -18.95387462, 15.07059417, 23.46713890, -2.30987854,…

$ PC29 <dbl> 41.5990398, 2.7744147, -52.1167153, -3.3138596, -0.8312010, 0.636…

$ PC30 <dbl> 8.619078e-13, 9.019729e-13, 8.957583e-13, 9.126588e-13, 8.833212e…

You'll notice that there are only 30 principal components, despite having thousands upon thousands of genes available to us. This is confusing! The reason is that any N samples can be described with N - 1 dimensions. Two dots can be described with a line (the first dimension), three dots can be described with a plane (the third dimension), etc. You'll also note that this has N principal components, NOT N - 1 principal components. I genuinely have no idea why this is, but the last component is usually negligible when considering variance explained.

Despite only having 30 principal components, each principal component is still a goulash of thousands of genes (our loadings) - note how each column is made of thousands of rows:

cell_loadings <- tidy(cell_pca, "loadings") |>

pivot_wider(names_from = PC, values_from = value, names_prefix = "PC")

# Only showing the first few components

cell_loadings[1:5]

# A tibble: 18,548 × 5

column PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 TSPAN6 0.0127 -0.00592 -0.000133 -0.000978

2 TNMD 0.00164 0.00269 0.000569 -0.00667

3 DPM1 -0.00267 0.00242 0.00677 -0.00493

4 SCYL3 0.0150 0.00290 0.00503 -0.000751

5 C1orf112 -0.00925 0.0101 -0.00640 -0.00517

6 FGR 0.0139 -0.00150 0.00243 0.00911

7 CFH 0.0131 -0.00149 0.00411 0.0109

8 FUCA2 -0.00817 0.00660 0.00135 -0.000318

9 GCLC 0.0146 -0.00618 -0.00112 0.00917

10 NFYA 0.0103 -0.00331 0.00191 0.00511

# ℹ 18,538 more rows

# ℹ Use `print(n = ...)` to see more rows

We can join our cell PCA back with its metadata by doing the same trick we did with our penguins data, but using the colData of our cell_rna DESeqDataSet instead. Note that we need to convert it to a tibble first:

col_data <- colData(cell_rna) |>

as_tibble(rownames = "row")

cell_pca_with_col_data <- left_join(col_data, cell_pca_coordinates, by = "row")

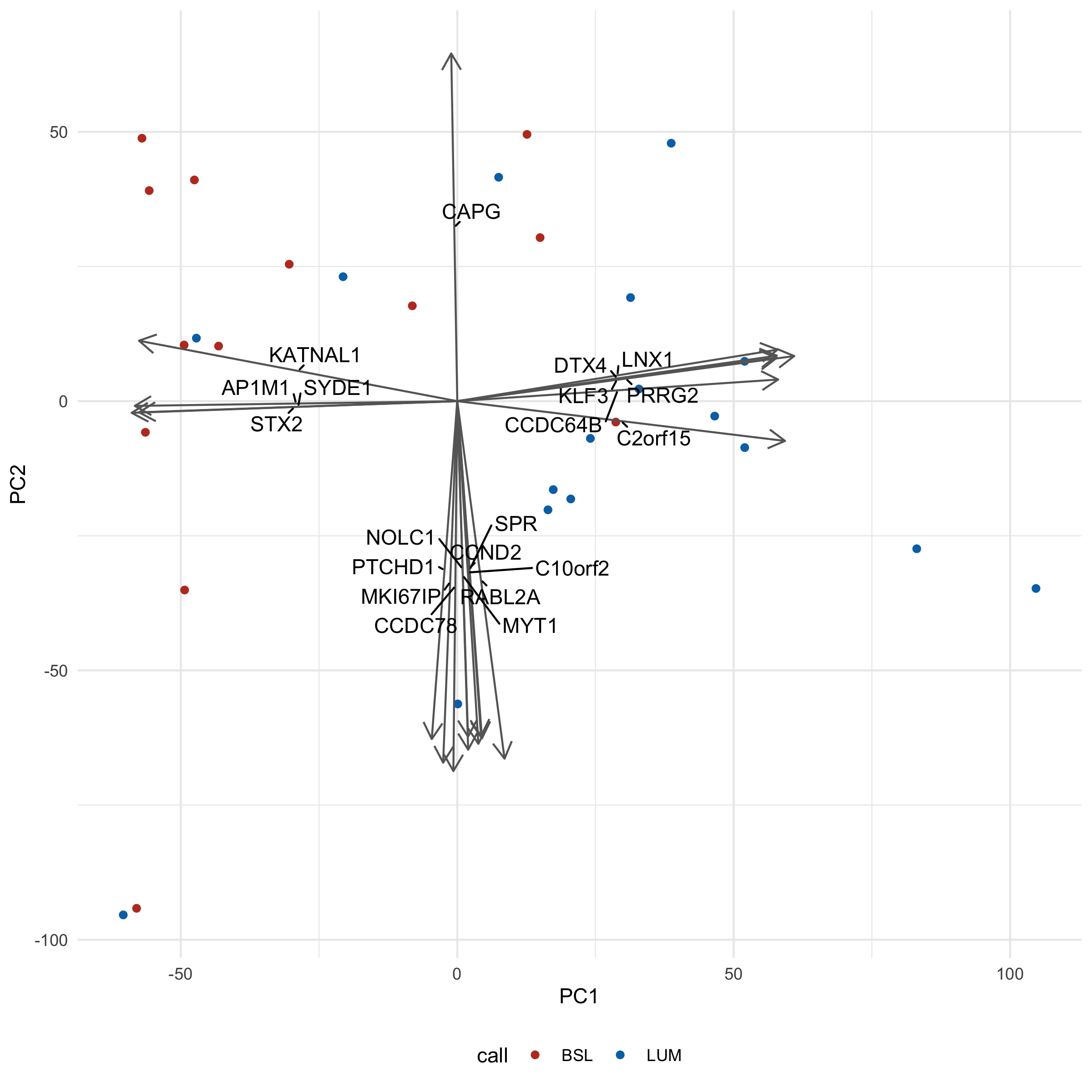

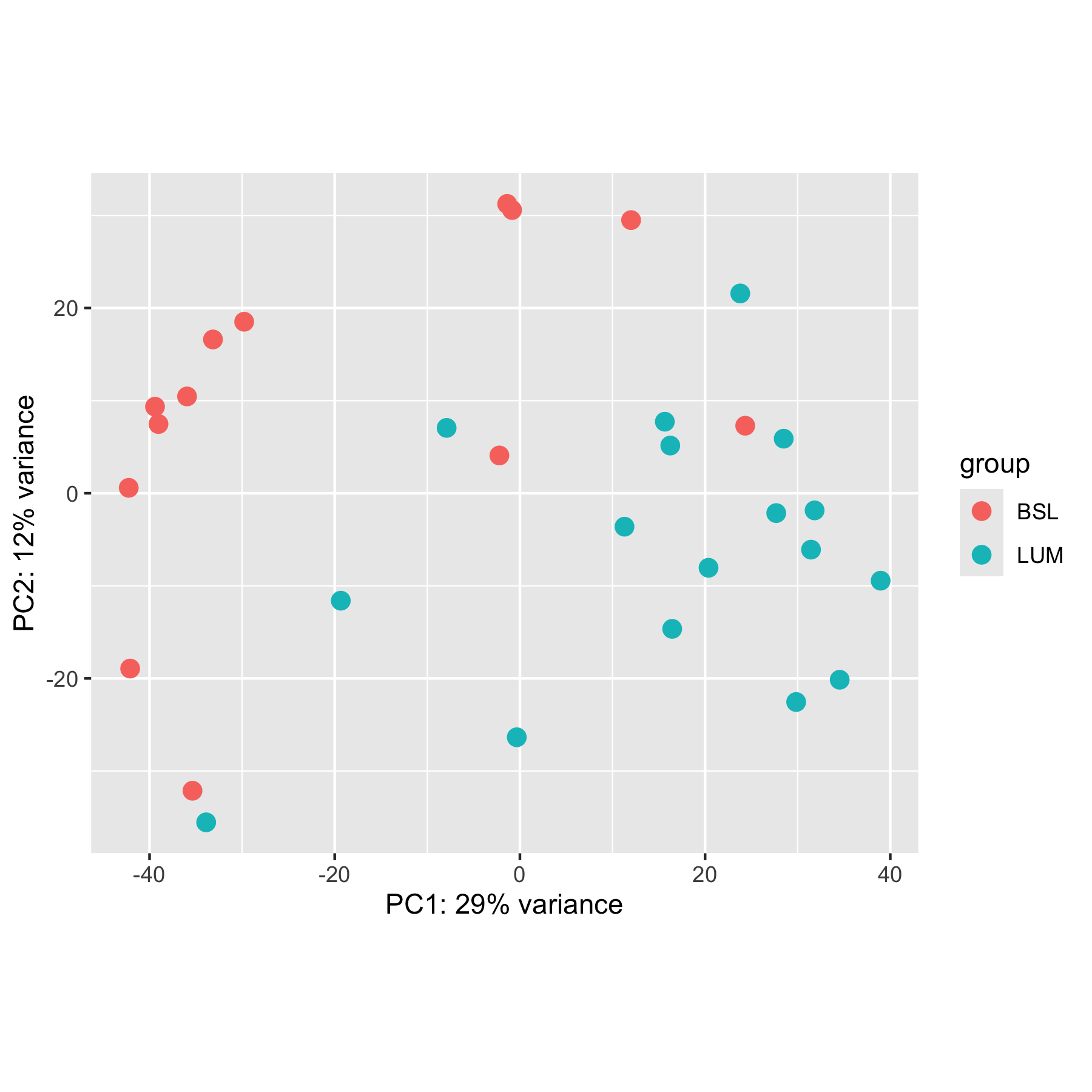

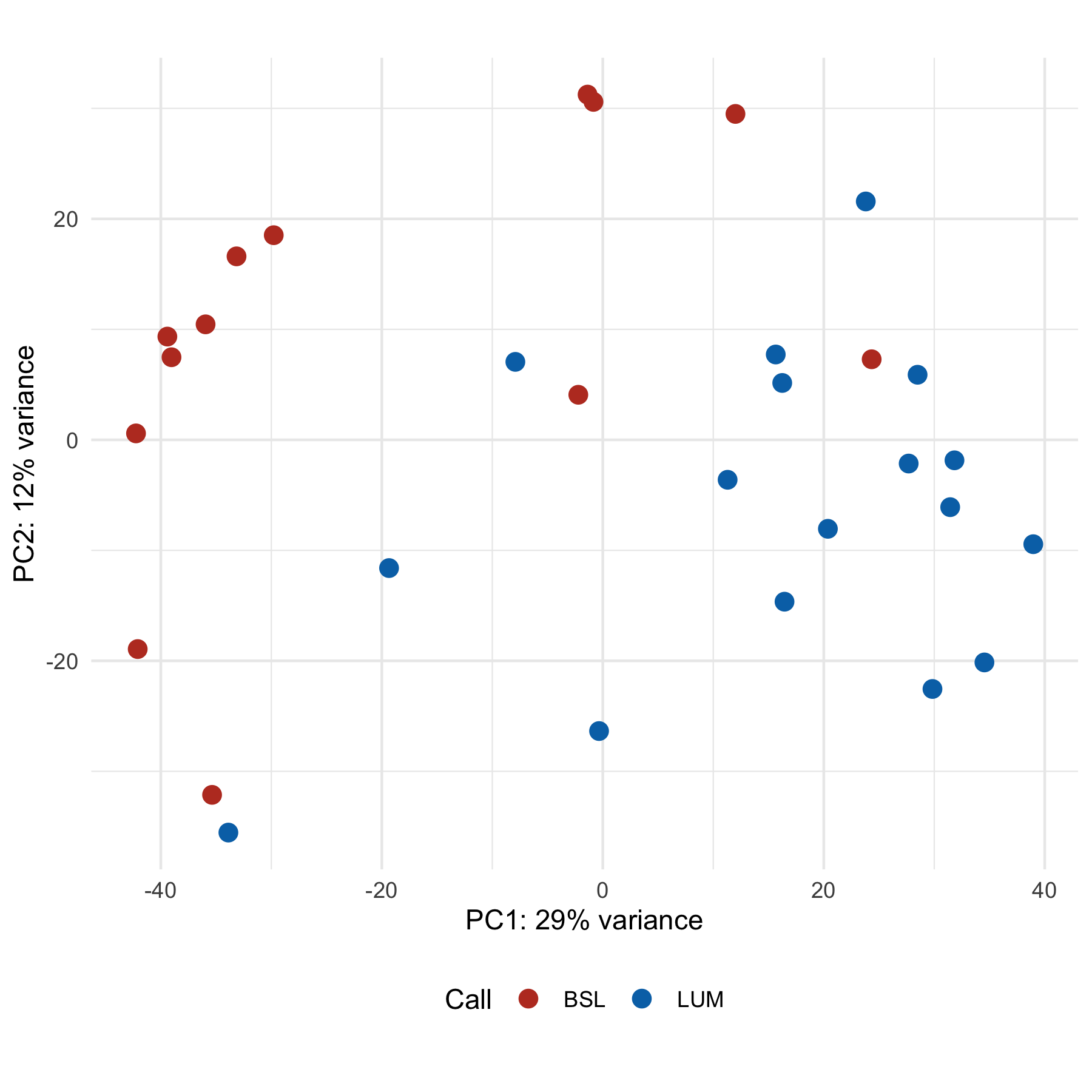

And we can use our handy functions to plot relatively painlessly:

filtered_loadings <- filter_loadings(cell_loadings, PC1, PC2, 10)

plot_pca(cell_pca_with_col_data, PC1, PC2, call, filtered_loadings, 3000)

You'll notice we had to crank up our loadings_scale_factor argument wayyy up (3000) - otherwise the arrows would be so small all you would see is the arrowheads.

Interpretation-wise, you'll note that there aren't really 'clusters' - more of a smear of dots. This might be more representative of biology itself, a gradient of a phenotype rather than distinct groups. We could validate with some kind of functional readout, like migration/invasion assays (good luck, those things are finicky).

An additional complication is that both the call and clade (which we've seen in the hclust chapter) are created based on gene expression data, so we're kind of cheating here. It would be more interesting to instead overlay some kind of phenotype, like IC50 to a drug, or, again, migration rate, and see if the 'gradient' pattern remains.

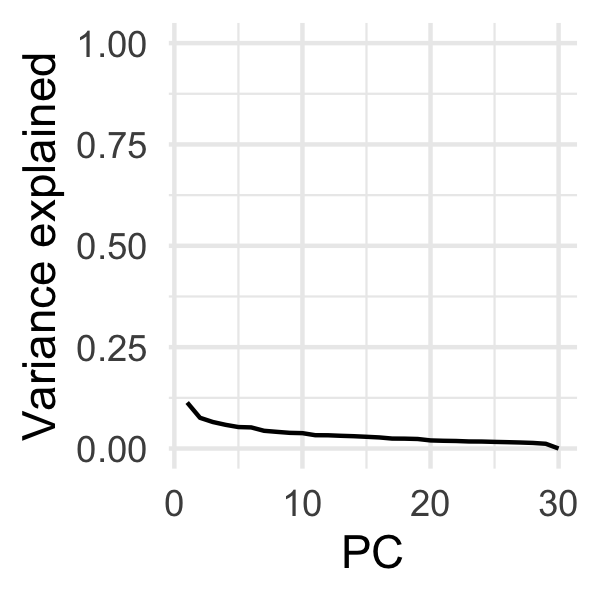

Making a scree plot, we also note that there isn't any readily apparent 'knee', and all PCs contribute relatively little:

var_explained <- tidy(cell_pca, "pcs")

ggplot(var_explained, aes(PC, percent)) +

geom_line() +

theme_minimal() +

coord_cartesian(ylim = c(0, 1)) +

labs(x = "PC", y = "Variance explained")

(Maybe a little knee at PC2?)

If our overlaid variable was an experimentally observed migration_rate rather than call, I would perhaps be inclined to experimentally determine if modulating those genes could influence migration, or perhaps impute the transcription factor for those genes (you could use GSVA + the C3 collection, for instance).

→ Other ways

I've shown you ways to make PCA plots that provide you with a reasonable amount of control, but there exist other, easier, but less flexible ways to do the same thing.

Base R has the `biplot` and `screeplot` functions:

biplot(pca)

screeplot(pca)

DESeq2 also has a built-in plotPCA function you can use. It must be on a DESeqTransform object, which are the things that come out of functions like vst and rlog.

transformed <- vst(cell_rna)

plotPCA(transformed, intgroup = "call", pcsToUse = 1:2)

Plus, since it returns a ggplot, we can modify it to some extent:

plotPCA(transformed, intgroup = "call", pcsToUse = 1:2) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position = "bottom") +

labs(color = "Call") +

scale_color_nejm()

By default, plotPCA only uses the top 500 highest variance genes, so the results you get from a standard PCA plot will likely look different unless you set ntop = Inf. Note how this plot looks different from the ones above.

One nice feature is that you can force it to return data rather than a plot, so you can be in control of the plotting:

plotPCA(transformed, intgroup = "call", pcsToUse = 1:2, returnData = TRUE) |>

# It returns all the colData columns - thinning up the return value for

# display purposes

select(1:4)

using ntop=500 top features by variance

PC1 PC2 group name

1A6 -1.376631 31.2472263 BSL 1A6

253JP -35.360950 -32.1292293 BSL 253JP

5637 -0.843214 30.5884901 BSL 5637

BV -33.884810 -35.5428876 LUM BV

HT1197 -2.215679 4.0794414 BSL HT1197

HT1376 15.652748 7.7261587 LUM HT1376

J82 -35.949146 10.4543889 BSL J82

RT112 38.961335 -9.4437031 LUM RT112

RT4 34.539660 -20.1439531 LUM RT4

RT4V6 29.836403 -22.5470613 LUM RT4V6

SCaBER 12.006323 29.4988844 BSL SCaBER

SW780 27.683299 -2.1442849 LUM SW780

T24 -39.408334 9.3462355 BSL T24

TCCSup -33.148222 16.6074099 BSL TCCSup

UC10 -7.913209 7.0581969 LUM UC10

UC11 -42.245562 0.5846359 BSL UC11

UC12 -19.344054 -11.6043159 LUM UC12

UC13 -39.032873 7.4769590 BSL UC13

UC14 31.441316 -6.0917340 LUM UC14

UC15 24.334233 7.2925341 BSL UC15

UC16 23.800955 21.5765319 LUM UC16

UC17 11.297020 -3.6134580 LUM UC17

UC18 -29.780013 18.5220710 BSL UC18

UC1 28.489529 5.8920060 LUM UC1

UC3 -42.091980 -18.9358037 BSL UC3

UC4 -0.337202 -26.3546891 LUM UC4

UC5 31.828498 -1.8516215 LUM UC5

UC6 20.372944 -8.0514637 LUM UC6

UC7 16.240251 5.1499101 LUM UC7

UC9 16.447366 -14.6468749 LUM UC9

However, this doesn't let you add loadings since it doesn't save the intermediate PCA data we used to extract the loading vectors. Another downside is that this only works with DESeqTransform objects, so for our penguins we wouldn't be able to use this.

→ Going further

You should also know that this isn't the only form of dimensional reduction. You may have seen some before - particularly t-SNE and UMAP. As I understand, these methods tend to be a bit more random - that is, without setting some kind of 'seed' you will get similar but distinct results each time you run it. However, I believe the preserve higher dimensional topology better - that is, things that are close together in this weird thousand-dimensional space tend to stay close to one another when plotted. These methods are common for things like single-cell RNAseq.

→ References

-

Allison Horst - who helped get the

penguinsdata into R - does a great PCA tutorial using the penguins data. - These two stackexchange answers helped me figure out why there were only 30 principal components when we have thousands of genes.

-

The DESeq2 Vignette has a tiny bit more information on

plotPCA